12.07.2012

12.07.2012ABOUT THE EDUCATIONAL PROBLEMS OF TURKEY’S ARMENIANCY

Ruben MelkonyanExpert at the Center of the Armenian studies, “Noravank” Foundation, the Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Oriental Studies at the YSU, the Candidate of Sciences (Philology), Assistant Professor

Education has always had a great importance in the Armenian lives; around the world, Armenians have founded and developed their national schools. Armenian community of Istanbul (called Bolis by Western Armenians) also traditionally valued education and it was no mere chance that by the end of the 19th century there were 90 Armenian schools in Bolis, of which 40 community-based and 50 private ones [1, p. 181]. In the same period 174 of the 454 Istanbul schools belonged to non-Muslims (Armenians, Greeks, Jews) and 16,248 pupils, which is about half of all schoolchildren in the city, were enrolled in these schools [2, p. 18]. By 1914 there were 64 functioning Armenian schools with 25,000 students [1, p. 181].

Turkish sources often regard the Armenian schools in the Ottoman Empire as sources of anti-state, that is, anti-Turkish ideas, with such sentiments even increasing in parallel to the activities of Western missionary organizations. Turkish sources contend that the ethnic and religious minorities, especially Armenians, believed the missionaries supported their “separatist aspirations” [3, p. 180]. Turkish authors with more extreme views argue that: “Western imperialist states who wanted to destruct and divide the Ottoman Empire, collaborated with ethnic minorities, the schools of which educated future clergymen and spies to work for them.”1

The Armenians’ right to have educational institutions and Armenian lyceums in the Republic of Turkey had been established by the Articles 40 and 41 of the Treaty of Lausanne [4, p. 24]. Armenian schools of Istanbul adjust their structures to match the changes occurring in Turkey’s general educational system and as of today they have three-tier schooling: kindergarten – 1 or 2 years, primary education – 8 years, high school (lyceum) – 3 years [4, p. 11]. Currently the educational problems of Istanbul’s Armenian community are part of the problems generally related to the education among the ethnic minorities in Turkey, and with this respect some interesting facts have been published in the 2009 report Combating Discrimination and Promoting Minority Rights in Turkey, which has been prepared with the support of the European Union. For instance, the data of this report clearly point to the diminishing numbers of ethnic minority schools and pupils, which is largely related to government policies predominantly aiming at assimilation. The section of the report about the situation in education is quite expressly titled as “Forgotten or Assimilated? Minority Rights in Education System of Turkey.”2 According to the data presented, in 1930-31 the number of minority schools in Tukey was 117, whereas by 1995-96 it has shrunk to 34 [5, p. 14].

In the first year of the Republic of Turkey, 1923, there were 47 Armenian schools in Istanbul [6, p.194], in 1972-73 their number decreased to 32 with 7,366 students, while in 1999-2000 there were 18 schools with 3,786 students and in 2009-2010 only 16 schools remained with 3029 students [4, p. 51]. As seen, in the period of 40 years (1972-2010) the Armenian community lost half of its schools and students. As Garo Paylan, an Armenian pedagogue from Istanbul stated: “Every year we lose around 150–200 students; if it continues this way, we will close down 6–7 schools in the coming years.”3

Falling number of the Armenian schools in Turkey is mainly related to decreasing number of students, which is caused by several reasons. However, it has to be noted that the Turkish government policies have contributed to emergence of various problems. For example, on March 3, 1924 the Law on Unification of Education was adopted in Turkey, which required bringing all educational institutions in line with laicism (secularity) principles. This caused serious difficulties for Istanbul Armenian educational institutions, since there were clergymen among the teachers of national schooling centers and this law prohibited their access to the schools. In addition, to be granted the right to teach, the teachers of the Armenian schools had to pass qualification exams before state commissions and obtain appropriate certificates. It has to be mentioned that item e) in Article 32 of the Ministry of Education No. 26810 decree specifically stipulated that “knowledge of Turkish language, as well as its correct and regulated use is a mandatory condition for Turkish citizens working in schools. If necessary, these teachers shall take a Turkish language examination” [7]. In 1937 Turkey’s Ministry of Education adopted a legal act stipulating that in the schools of ethnic minorities the deputy principals must be ethnic Turkish, in order to “bring up the students in line with the Turkish culture” [6, pp. 195-196]. Interestingly, quite often nationalistically oriented people are appointed as deputy principals. In minority schools the subjects History of Turkey and Civil Defense are taught by ethnic Turkish specialists. The organization and control of teaching process in minority schools is regulated by the Ministry of Education decree No. 26810 on private educational institutions, which is based on the Law on Special Educational Institutions No. 5580 of February 8, 2007.

In the context of the Turkish bid for the European Union membership, series of human rights studies were carried out in the country. One of such studies contains recommendations directed to the Turkish government regarding the problems in ethnic minority schools, including abolishment of the mandatory requirement for minority school deputy principals and Turkish culture teachers to be ethnic Turks [8].

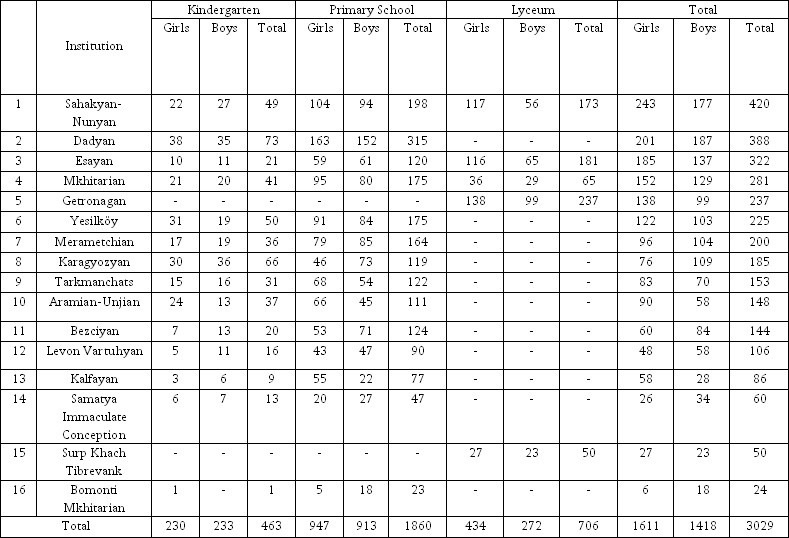

As mentioned above, currently there are only 16 Armenian schooling centers in Istanbul. In the recent years Pangalti Immaculate Conception and Nersessian-Yermonian primary schools were closed due to decreased number of students and financial problems. The table below represents the most recent data on Istanbul Armenian schools and number of students that have been prepared by Silva Kuyumjian, years-long principal of the Istanbul Getronagan High School4 [4, p. 50].

Gradual deterioration of situation with Istanbul Armenian schools has some underlying reasons, some of which are as follows:

1. One of the most troubling problems is the year-to-year decline of the number of students5. Years ago most of the Armenian parents used to send their children at least to Armenian primary schools where they could learn Armenian in parallel with gaining general knowledge [4, p. 28]. The situation is different today and many parents prefer to send their children to Turkish, English, German schools (lyceums), where the education quality is quite high [9, p. 22], and later makes it easier to get admitted to universities.

Decrease of the student numbers is also directly related to emigration of Istanbul Armenians. It is worth mentioning that the number of Istanbul Armenian school students remained the same or did not decline drastically in 1960s, because many Armenians moved from provinces to Istanbul and sent their children to Armenian schools.

2. Problems of Armenian schools include lack of textbooks in Armenian and their quality. Moreover, it is prohibited to teach by textbooks published abroad (e.g. in Armenia).

3. Qualification level of the teachers is also an important issue. Speaking Turkish increasingly in everyday life and in families does not help the matter either and it has to be noted that unfortunately, Armenian language constantly rolls back in the Armenian schools. Teachers do not have good enough command of Armenian to be able to teach in the mother tongue, whereas students are not known to be too keen about this. As Silva Kuyumjian has put it; “The level of the Armenian language teaching has dropped to an extent that it is no longer possible to meet a young person who is fluent in Armenian”[4, p. 13]. Regarding the decline of the Armenian language level it was even once opined during a community meeting that Armenian has become an “intermediate language” or “having a status weaker than a mother tongue, but stronger than a foreign language” [10]. Currently, in some of the community’s churches preaching has to be done also in Turkish so as to be understood by the Turkish speaking attendees. Findings of a recent sociological survey indicate that Armenian language is used only by 18% of the Istanbul Armenian community [6, p. 309].

Silva Kuyumjian notes that prior to 1970s teachers in Istanbul Armenian schools were highly qualified and had excellent command of the mother tongue. The mentees of this generation who succeeded them were considerably less proficient in command of the mother tongue and this adversely affected the teaching quality and students. Hence, these teachers preferred teaching in Turkish over deficient teaching in Armenian. Silva Kuyumjian’s following deliberation is quite indicative of the Istanbul Armenian schoolteachers’ professional level: “Today, we have no male teachers in our primary schools, and females just teach as a side occupation to their housewife activities” (bold script by the author of this paper – R.M.) [4, p.19]. It has to be added that persons who are not Turkish citizens do not have the right to teach in Turkey’s minority schools. The legislation stipulates state control to be exerted both over the subjects taught and school management, including appointments to teacher positions.

Educational Problems of the Republic of Armenia

Citizens Living in Turkey

In the recent years a problem has surfaced related to the education for children of the Republic of Armenia citizens illegally residing in Istanbul. Representatives of the Armenian community have brought the issue to the attention of Turkish authorities and it is expected that there might be positive changes in this matter starting as early as 2011-2012 academic year. Meanwhile, before the problem is addressed, since 2003 an underground Armenian school functions in the basement of the Gedikpaşa Armenian Evangelical Church, where around 60 Armenian children study in 1st to 5th grades6. The idea to create a school for children of Armenian nationals belongs to Alex Uzuroglu, an Istanbul Armenian and Heriknaz Avagyan, a pedagogue from Armenia residing in Istanbul. They have made a request to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople to provide premises, but their request has been denied. Afterwards, Rev. Krikor Agabaloglu, Pastor of the Armenian Evangelical Church extended a helping hand and offered them space. Interestingly, as per the information obtained, specialists with higher pedagogical education teach at this underground school in accordance with Republic of Armenia school curricula, and the walls are decorated with the Armenian flag, map and national anthem7.

Educational Problems of Mixed Parentage Children

Endogamy is widespread among Armenians and efforts are made maintain it especially outside Armenia. The Istanbul community has also paid much attention to endogamy, but a number of developments affected the process and today the number of intermarriages outside the community gradually increases, and there are even some opinions that they comprise as many as 40-50%. This brings concerns in the sense that intermarriages result in many problems related to religious affiliation, national self-consciousness and of course, education. With increasing occurrences of mixed marriages the Armenian community on one hand, tries to get adapted to the situation arisen, and on the other hand, to find solutions for emerging dilemmas among which various educational issues are important. The problem is, to enroll in an Armenian school both parents of a child must be members of the Armenian Apostolic Church and actually the law forbade mixed parentage children to attend Armenian schools even if they wished so. However in 2010 the Turkish Ministry of education issued a notice which significantly slackened this requirement, stating that only one of the parents had to be an Armenian Christian. It is anticipated that this measure might change the situation and positively affect the Armenian schools in terms of the number of students. Moreover, Istanbul Armenian schools admitted the first students of mixed parentage, yet this process has another interesting aspect. As it has become known from different sources, among the children admitted to the Armenian schools there are some born to parents one of which is Muslim. Karekin Barsamyan, Principal of the Mkhitarian Armenian High School has noted in an interview to Hurriyet Daily News reporter of Armenian descent Vercihan Ziflioğlu: “A number of the school’s students were registered as Muslim on their identity cards. Regardless of what their identity cards say, these kids are receiving an Armenian-Christian education and they will decide upon their identities themselves in the future.”8 Remarkably, there are some Armenian schoolchildren one of whose parents is an Armenian Christian and the other one is a descendant of forcibly Islamized Armenians. For example, 34 years old Aylin descends from an Armenian family from Mush converted to Islam in 1915. She is married to an Armenian Christian man and has a 9 years old son who attends an Armenian school. The mother’s family live as devout Muslims, whereas the father’s kin are Christians, and this circumstance causes identity crisis type of experiences for the 9-year-old boy. Nevertheless, the family has decided to send the boy to an Armenian school, and Aylin, the descendent of forcibly Islamized Armenians brings the following argument for that: “I could not learn about my language and my culture. I want him to at least have a notion about it”.9

1 Kılıç R., Osmanlı Türkiye’sinde azınlık okulları (19. yüzyıl), http://www.hyetert.com/yazi3.asp?s=1&Id=374&DilId=1

2 Unutmak mı, asimilâsyon mu? Türkiye’nin eğitim sisteminde azınlıklar, http://www.hyetert.com/yazi3.asp?s=1&Id=409&DilId=1

3Ibid.

4 The (–) sign in the Table indicates that there is no kindrgarten, primary school or liceum (high school) in the given school.

5 Data provided by Silva Kuyumjian, Principal of the Istanbul Getronagan High School, point to the gradual, and unfortunately, steady decline of Istanbul Armenian school students over the last ten years. These data in accordance with academic years are as follows: 2000-2001 – 3,711 students, 2001-2002 – 3,530, 2002-2003 – 3,401, 2003-2004 – 3,289, 2004-2005 – 3,210, 2005-2006 – 3,162, 2006-2007 – 3,099, 2007-2008 – 3,023, 2008-2009 – 3,045, 2009-2010 – 3029 [4, p. 47].

6 http://www.news.am/arm/news/52487.html

7 Ibid.

8 Ziflioğlu V., Ermeni Azınlık Okullarında Karma Evliliklerden İlk Jenerasyon http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/n.php?n=armenian-schools-open-doors-to-a-different-audience-2011-01-27

9 Ibid.

References and Literature

- Հայ Սփյուռք հանրագիտարան, Երևան, 2003:

- Alkan M., Tanzimat’tan Cumhuriyet’e modernleşme sürecinde eğitim istatistikleri, Tarihsel istatistikler dizisi, Devlet İstatistik Kurumu, sayı 6.

- Haydaroğlu P., Osmanlı İmparatorluğunda yabancı okullar, Ankara, 1990.

- 4. Գույումճեան Ս., Ակնարկ մը` ստանպուլահայ վարժարաններու իրականութեան, Ստանպուլ, 2010:

- Cumhuriyet dönemi İstanbul istatistikleri, Eğitim İstanbul I (İlk, Orta, Lise, 1928 - 1996), İstanbul Külliyatı, İstanbul, 1998.

- Özdoğan G., Üstel F., Karakaşlı K., Kentel F., Türkiye’de Ermeniler: Cemaat-Birey-Yurttaş, İstanbul, 2009.

- T.C. Resmi Gazete, 8 Mart 2008, sayı: 26810.

- Ակօս, 14,12, 2007:

- Լոքմագյոզյան Տ., Ստամբուլի հայկական դպրոցները, «Գլոբուս» վերլուծական տեղեկագիր, Երևան, 2008, թիվ 3:

- Agos, 11,10, 1996.

- Kılıç R., Osmanlı Türkiye’sinde azınlık okulları (19. yüzyıl), - http://www.hyetert.com/yazi3.asp?s=1&Id=374&DilId=1

- Unutmak mı, asimilâsyon mu? Türkiye’nin eğitim sisteminde azınlıklar, - http://www.hyetert.com/yazi3.asp?s=1&Id=409&DilId=1

- http://www.news.am/arm/news/52487.html

- Ziflioğlu V., Ermeni Azınlık Okullarında Karma Evliliklerden İlk Jenerasyon http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/n.php?n=armenian-schools-open-doors-to-a-different-audience-2011-01-27

Return

Another materials of author

- ON MANIFESTATIONS OF SELF-ORGANIZATION OF THE ARMENIANS IN TURKEY[29.05.2012]

- THE ISSUE OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE AND MODERN TENDENCIES OF TURKEY’S POLICY[14.05.2012]

- THE STUDY OF THE ISSUE OF ISLAMIZED ARMENIANS IN TURKEY: PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS[12.04.2012]

- THE ISSUE OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE IN THE TURKISH PARLIAMENT [08.12.2011]

- ON SOME TENDENCIES OF CONTEMPORARY TURKISH HISTORIOGRAPHY[17.11.2011]

- “THE BEST TREATISE OF THE YEAR” ANNUAL CONTEST[12.10.2011]

- ON MODERN TENDENCIES IN TURKISH ETHNIC POLICY[06.10.2011]

- DEVELOPMENTS AMONG THE ASSIMILATED ARMENIANS IN TURKEY: DYARBAKIR[28.07.2011]

- THE MODERN ISSUES OF THE CIRCASSIANS IN TURKEY [07.07.2011]

- ON THE MODERN TENDENCIES IN THE “ARMENIAN POLICY” OF TURKEY [20.06.2011]