02.04.2012

02.04.2012ARMENIA AND CHINA—CASE FOR A SPECIAL PARTNERSHIP

By Simon SaradzhyanFellow, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

Summary

This article will take stock of the Armenian-Chinese relations to discern whether Yerevan has been effective in its response to the ongoing rise of the Middle Kingdom as the two countries prepare to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations this April. The article will compare Armenia’s policy vis-à-vis China to that of Georgia and Azerbaijan and identify areas where Yerevan could be doing more to advance the bilateral relationship. The article will conclude with specific recommendations on how Armenia can transform the relationship with China into a special partnership that would increase both Armenia’s benefits from the rise of China and China’s stake in the peaceful development of Armenia.

The Rise of China

There is hardly an international affairs expert left who has not lamented the unpredictability of the post–Cold War world (even if Francis Fukuyama might still be claiming that history has ended). But there is one trend in the international affairs that most of these experts predict will probably continue for years to come: the rise of China. For many of them, the question is no longer whether China will become the world’s dominant economic power, but rather when this will occur. The International Monetary Fund and Goldman Sachs are betting on, 2016 and 2030 respectively.1 The Middle Kingdom already leads the world in such spheres as exports, manufacturing, and foreign exchange reserves. As for those who may have doubts about how far the Chinese economy has progressed technologically since Mao Zedong urged Chinese peasants to make iron in backyard furnaces, they should consider the following fact: the world’s fastest supercomputer in 2010 was China’s Tianhe-1A.

China’s rise is already causing a realignment of geopolitical balances across the post–Cold War world, in which economic might and abundance of human capital increasingly matter more, while nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles lose value, prompting both great powers and smaller nations to scramble to advance ties with the Middle Kingdom. China has already become the largest trading partner of such powers, as Japan, Russia, and India. It is also the largest trading partner of Latin America and Africa as well as the second largest trading partner of the United States.

Post-Soviet Armenia’s China Policy: Diplomacy Pays Off

The 20th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between post-Soviet Armenia and China offers a good opportunity to review the bilateral relationship in order to determine whether Yerevan has been effective and pro-active enough in its response to China’s resurgence.

Even a superficial review of Armenia’s policy vis-à-vis China would reveal that Yerevan has been actively trying to advance the relationship with Beijing, paying particular attention to bilateral trade, which almost doubled in 2009–2010, with China becoming Armenia’s largest trading partner in 2010.2 The following year saw Russia retake the top spot in the list of Armenia’s trading partners, but China still generated more trade with Armenia than neighboring Iran in 2011.3 The current Armenian-Chinese trade statistics look especially rosy when one recalls that the volume of trade between the two countries was a meager $370,000 less than 15 years ago.4 However, Armenia still lags behind both of its South Caucasian neighbors in trade with the Middle Kingdom, even though the latter was neither among Azerbaijan’s or Georgia’s top five trading partners in 2010.5 Armenia’s exports to and imports from China totaled $16 million and $405 million in 2011.6 In comparison, Georgia’s trade with China generated $553 million in 2011.7 As for Azerbaijan, its imports of Chinese goods totaled $628 million in 2011, according to the republic’s national statistics agency.8 Notably, China is absent from the Azeri statistics agency’s list of major importers of goods and services from Azerbaijan, although a number of Chinese companies have been reported to have signed agreements to develop onshore oil fields in Azerbaijan.9 The obvious explanation for this disparity is that the economy of Armenia is smaller in size than that of Azerbaijan and Georgia, which should come as no surprise, given that Armenia is not only landlocked, but also continues to endure a semi-blockade.10 Armenia also lacks energy resources, which generate a steady flow of cash for Azerbaijan, and trails behind Georgia in economic and public administration reforms.

Nevertheless, the continuing growth in Armenia’s trade with China generates optimism, demonstrating that the personal commitment by the Armenian leadership to advance Yerevan’s relationship with Beijing is literally paying off. That commitment is best illustrated by the fact that all of Armenia’s presidents and foreign ministers have visited China.

All in all, top Chinese and Armenian government officials have paid over 30 visits to each other’s countries since the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of Armenia established relations on April 6, 1992. Armenia's incumbent president, Serzh Sargsyan, has paid two working visits to China, including a trip to the Expo 2010 in Shanghai, where he opened the Armenian pavilion and pushed for further expansion of bilateral trade ties during a meeting with Chinese President Hu Jintao. Sargsyan also traveled to China as an interior minister in 1998 and then as a defense minister in 2001. In comparison, only two out of post-Communist Azerbaijan’s seven presidents—Heydar Aliyev and his son Ilham Aliyev—have traveled to China. The elder Aliyev traveled once, while his son made the trip twice.11 Of the three heads of the post-Soviet Georgian state, only incumbent president Mikheil Saakashvili has paid a visit to China, according to the Georgian embassy in Beijing.12

That the Armenian leadership values the relationship with China is clear not only from the frequency of the visits, but also from the reception given by the hosts to the guests. A visiting Chinese official is usually granted the opportunity to meet the president of Armenia and the republic’s top ministers, even if he or she is not a top dog—as was the case when an assistant to the Chinese foreign minister came to Yerevan in April 2003.13 Chinese leaders have also paid appropriate attention to Armenian officials visiting Beijing. Armenian presidents and prime ministers—who have visited China six times in the past 20 years— have invariably met their Chinese counterparts during all but one of such visits.14

China’s continuing rise requires Yerevan to be ever more energetic and persistent in engaging Beijing not only diplomatically, but also economically. Armenian leaders need to be both pro-active and relentless if they want to transform the Chinese-Armenian relationship into a special partnership in spite of the existing geographic and economic constraints. Otherwise, Armenia won’t matter to China much more than it does now, when Chinese strategists ponder how long a hike in world oil prices will last if the Karabakh conflict heats up.

Taking a Cue from Two Ancient Peoples’ Special Partnership

Of, course, it may seem incredulous to some that China would agree to forge a special relationship with a small state, which a) is located thousands of miles away; b) has had a diaspora in the Middle Kingdom for centuries but established diplomatic relations with Beijing only 20 years ago; and c) lacks natural resources but has hostile neighbors that possess oil and gas that energy-hungry China prizes so much.

To such skeptics, I say: Look at Israel. In fact, the similarities between Israel’s and Armenia’s position vis-a-vis China are so striking that I would argue some of the compliments that the Israeli and Chinese statesman have recently exchanged on the newly formed partnership of the two ancient peoples might as well have come from a transcript of a Chinese-Armenian summit.15 Such complimentary rethoric doesn’t appear out of thin air. It is based on the solid economic relationship that Israel has managed to build with China after the latter agreed to establish diplomatic relations with the Jewish state in January 1992. Since then, bilateral trade has increased by 200 times and now stands at $10 billion a year, with China being Israel’s third-largest export market.16 No wonder international affairs experts talk about a special partnership between Beijing and Tel Aviv.

It goes without saying, of course, that the Armenian economy is far less advanced than that of Israel, but what the Jewish state is exporting to China is instructive for selecting what Armenia should be selling to the Middle Kingdom to minimize the share of shipping in overall cost. Israel exports to China mostly high-value goods such as telecommunications and information, solar energy equipment, and pharmaceuticals.17

Proposal for a Great Leap Forward in the Bilateral Relationship

When trying to build a special partnership with China, Armenian leaders should first and foremost focus on deepening bilateral economic cooperation. Without deep economic ties, Armenia’s relationship with China will remain vulnerable to disruption no matter how much scholars of the past Great Games theorize about how Beijing’s lingering problems with Uighur separatists should keep the Middle Kingdom committed to preservation of a viable Armenian state as the only geographical obstacle to pan-Turkism.

One obvious way to deepen economic cooperation is to attract more investment from China, which holds a mind-boggling total of $3.2 trillion in foreign exchange reserves—the world’s largest—and which spends tens of billions of dollars on foreign assets every year. China has been investing an average of more than $40 billion in non-bond assets abroad over the past several years, but Armenia has been so far able to attract only a small fraction of this investment. Armenia attracted $1.4 billion in Chinese investment from 1992 to 2010 and another $2.7 billion in the first few months of 2011, according to one estimate.18

One way for the Armenian government to entice Chinese companies into more bilateral trade is to agree to conduct more transactions in Renminbi, which the Chinese government seeks to promote as one of the world’s reserve currencies.

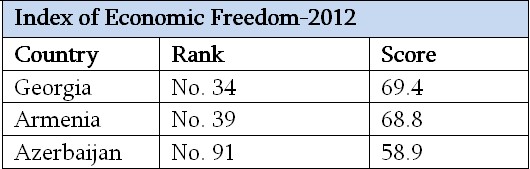

The Armenian government will also be more successful in attracting Chinese investments if it improves the general business climate in the country. It is easier to do business in general and to conduct import-export operations in Armenia than in Azerbaijan, according to World Bank rankings. But at the same time, Armenia trails behind Georgia in the same World Bank rankings—an indication that more could be done to liberalize the Armenian economy, which continues to suffer from oligopolies and formidable corruption. (See Appendix I for charts measuring attractiveness of the business environment in Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan for investment.)

Armenia should try particularly hard to draw Chinese investors into developing export-oriented sectors that produce goods or services, which are of high value but in which shipping accounts for a lower-than-average fraction of the total cost—such as information technology.19 Such projects will help to diversify Armenia’s trade with China, which is now mostly limited to exports of minerals and imports of consumer goods, food, and machinery.20

Anyone unsure how much impact a deepening of economic ties could have not only on Armenia’s bilateral relationship with China, but also on Beijing’s position on issues of vital interest for Yerevan at international forums, should take a cue from how the depth of the Chinese-Iranian economic relationship affects the position this veto-yielding member of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) takes on Tehran’s nuclear program at the UNSC and the International Atomic Energy Agency.21

Another aspect of the bilateral cooperation that the Armenian government should pay greater attention to is military-technical cooperation. Yerevan should consider following up on recent purchases of arms from Beijing by proposing a licensed production of such Chinese defense systems in Armenia that would expand the Armenian state’s indigenous capacity for maintaining a robust deterrence potential.

The Armenian armed forces should also develop other aspects of cooperation with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), such as military-to-military contacts. Armenia’s ancient commander-in-chief Vardan Mamikonyan may or may not have descended from the Han dynasty, but future generations of Armenia’s military leaders will benefit from being sent to expand their knowledge at military academies of a country that has developed the art of war for millenia and possesses the world’s third largest nuclear arsenal. These ties—which may come in especially handy in an emergency—would develop to a greater extent if the two militaries establish regular exchanges of delegations and conduct joint exercises.22 So far, such military-to-military contacts between PLA and Armenian armed forces have not been frequent. Armenia’s defense ministers and chiefs of the general staff have been less-frequent visitors than their commanders-in-chief. They have paid four visits to Beijing in the past 15 years while visiting Moscow every year. China’s preoccupation with its own territorial problems and Beijing’s aversion to publicly taking sides in the South Caucasus helps to explain why the Armenian-Chinese military diplomacy has been rather limited. Armenia’s natural choice of Russia as its main strategic partner, if not a guarantor, is also a factor, as are more than 5,000 kilometers that separate Armenia from China.

There are, of course, other actions that the Armenian leadership could take to increase and institutionalize China’s stake in peaceful and steady development of Armenia without undermining its traditional partnership with powers such as Russia, the European Union, and the United States.23 (See Appendix II for comparisons of these powers that are instructive for Armenia’s foreign policy choices).

Armenia is a small country, but its vote in such key international forums, as the UN General Assembly, is as good as everyone else’s. Supporting Beijing’s initiatives—such as a ban on deployment of weapons in space, a differentiated approach to global climate policy, and World Bank and IMF reforms—at these forums would make this permanent member of UNSC more supportive of Yerevan on issues that matter to Armenia most.

A Chinese-Armenian summit would provide a perfect opportunity to achieve a great leap forward in bilateral cooperation. Armenian diplomats should, therefore, exert maximum efforts to organize Sargsyan’s first state visit to China before a rotation of power occurs in the Middle Kingdom.24 The Armenian leader should meet both Hu and Vice President Xi Jinping before the latter becomes the next president in early 2013. The summit should elevate the status of the existing Armenia-China intergovernmental commission to that of a bilateral presidential commission, which would feature working groups headed by relevant ministers and which would hopefully repeat the success of two similar commissions that the United States and Russia have established. Most of the projects I propose above and below could be pursued within the framework of such a commission. During the summit, Sargsyan should also secure Xi’s consent to become the first Chinese leader to visit Armenia.

Nor should Armenia shy away from expanding the people’s diplomacy, promoting educational exchanges between the two countries to ensure that not only the current, but also future, leaders of China can do much more vis-à-vis Armenia than simply locate it on the map.25 Establishment of the Confucius Institute in Yerevan at the Yerevan State Linguistic University of Armenia in partnership with China’s Shanxi University in 2008 was a step in the right direction. It should be followed by the establishment of an Armenian institute in China, preferably on the premises of a top public administration or diplomatic graduate school.

Armenians living abroad could, of course, play a role in promoting relations between China and Armenia, especially in the economic sphere.26 The Armenian diaspora in China is small, but there are a plenty of Armenian businessmen that live in other countries and do business with Chinese companies. Armenia’s foreign affairs and diaspora ministries should engage such businessmen in efforts to secure joint Chinese-Armenian financing of development projects in Armenia that would edge the two nations closer to the special partnership I propose.

Thinking Outside the Box

The proposed mission of establishing and maintaining a special partnership with China— whose daily subway commuters in the nation’s capital outnumber the population of Armenia—would prove impossible without unorthodox approaches.

Hence, in addition to pursuing the useful but customary projects proposed above, the Armenian leadership should also think of outside the box. To advance military ties, for instance, the Armenian leadership could consider embedding an Armenian unit into a Chinese contingent the next time the PLA decides to commit troops for a UN operation. If Armenian peacekeepers can serve under the German command in a NATO-led operation in Afghanistan, then why can’t they serve under the Chinese command in a UN mission?

Armenian policymakers looking for unorthodox ideas on how to make Armenia matter much more in the eyes of their Chinese counterparts should also take a cue from Beijing’s reaction to treatment of Chinese diasporas in third countries. If loss of income by several hundreds of Chinese traders caused by closing of a Moscow market warrants a note from China’s foreign ministry, then one might ask: Would China have a greater stake in Armenia’s security and prosperity if there were several thousands of Chinese peasants working on those Armenian agricultural lands that suffer from shortage of labor? The answer to that question is obvious, as is the fact that Armenia’s chances of peaceful, sustainable development will be enhanced greatly if it becomes a special, if not indispensable, partner of the rising superpower.

Simon Saradzhyan is a native of Nagorny Karabakh’s Shahumian district. The author would like to thank Temirbek Aituganov, ex-director of the public debt department at the Finance Ministry of Kyrgyzstan, Emil Sanamyan, Washington editor for The Armenian Reporter; and Ali Wyne, research associate at Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs; for their advice.

Appendix I. Business Climate in Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan:

A total of 184 countries ranked. The higher the score, the better the business climate. Source: Heritage Foundation.

A total of 183 countries ranked. The higher the score, the lower the corruption. Source: Transparency International.

A total of 183 countries ranked. The higher the ranking, the easier to do business. Source: World Bank.

Appendix II. Comparing Present and Future of Prospective Partners:

Sources: World Bank, Goldman Sachs, Economist Intelligence Unit.27

1In 2016, China’s GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms will be $18,976 billion, while the United States’ GDP in PPP terms will be $18,807, according to the IMF’s forecast. (World Economic Outlook Database, IMF, April 2011); Goldman Sachs predicts that China’s GDP will total $25,610 billion in 2030, while America’s GDP will total $22,817 billion that year at market exchange rates. (Dominic Wilson and Anna Stupnytska, Global Economics Paper No. 153, Goldman Sachs, March 28, 2007)

2“Armenia, China to Hold High-Level Business Forum,” Xinhua, April 7, 2011.

3China generated 7.7% of Armenia’s external commercial turnover in 2011, compared to Russia’s 20.3%, Germany’s 7.4%, and Iran’s 5.9%. (Country Report Armenia, 1st Quarter 2012 Main Report, Economist Intelligence Unit, February 2012)

4Trade volume for 1997. “Kitaisko-Armyanskie Otnoshenia” (“Chinese-Armenian Relations”), web site of the People’s Republic of China’s embassy to the Republic of Armenia, undated. Available at http://am.chineseembassy.org/rus/zygx/t392051.htm. Accessed on March 14, 2012.

5Azerbaijan’s largest trading partners in 2010 were Italy (26.8%), the U.S. (8.4%), Germany (7.1%), France (6.7%), Czech Republic (4.9%), and Russia (4.4%). Azerbaijan, CIA World Fact Book, undated. Available at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/aj.html. Accessed on March 14, 2012. Georgia’s largest trading partners in 2010 were Turkey (15%), Ukraine (9.2%), Azerbaijan (8.5%), Russia (6.5%), and Germany (6.1%). Georgia, CIA World Fact Book, undated. Available at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gg.html. Accessed on March 14, 2012.

6External trade database by country in 2011, web site of the National Statistical Service of Republic of Armenia, undated. Available at http://www.armstat.am/en/?nid=380&thid[]=156&years[]=2011&submit=Search. Accessed on March 14, 2012.

7Georgia’s imports from China totalled $525 million in 2011, while its exports totalled $29 million. Decimals rounded to closest whole number. Main Statistics External Trade and FDI External Trade, web site of the National Statistics Office of Georgia, undated. Available at http://www.geostat.ge/index.php?action=page&p_id=137&lang=eng. Accessed on March 14, 2012.

8Foreign Trade Relations of Azerbaijan for 2011, web site of the Ministry of Economic Development of Azerbaijan, undated. Available at http://www.economy.gov.az/eng/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=641.Accessed on March 14, 2012. No estimates of Azerbaijan’s exports to China are available at this site.

9Fariz Ismailzade, “Azerbaijan and China Move to Increase Security and Economic Cooperation,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, March 21, 2005.

10At current prices Armenia’s GDP in 2011 was $9.3 billion, Georgia’s was $11.6 billion, Azerbaijan’s was $51.7 billion. World Bank Data Bank, web site of World Bank, undated. Available at http://databank.worldbank.org/ddp/editReport?REQUEST_SOURCE=search&CNO=2&country=&series=SM.EMI.TERT.ZS&period=. Accessed on March 14, 2012.

11Arguably the Aliyevs’ predecessors in the early 1990s lost the Azeri presidency too quickly to visit all the countries they may have wanted to.

12Relations between Georgia and the People’s Republic of China, web site of the Republic of Georgia’s embassy to the People’s Republic of China, undated. Available at http://china.mfa.gov.ge/index.php?lang_id=ENG&sec_id=552. Accessed on March 14, 2012.

13“Kitaisko-Armyanskie Otnoshenia” (“Chinese-Armenian Relations”), web site of the People’s Republic of China’s embassy to the Republic of Armenia, undated. Available http://am.chineseembassy.org/rus/zygx/t392051.htm. Accessed on March 14, 2012.

14The only exception was when President Sargsyan attended the opening of the Olympic Games in Beijing in 2008. He had no public meetings with the Chinese leaders during that visit.

15“We are two ancient peoples whose values and traditions have left an indelible mark on humanity,” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said during his visit to Beijing this past January. China's ambassador to Israel Gao Yanping returned the compliment several days later, saying: “As two ancient civilizations, we have a great deal in common. Both of us enjoy profound histories and splendid cultures.”Oren Kessler, “Shalom, Beijing,” Foreign Policy Magazine March 13, 2012.

16Ibid.

17Ibid.

18“Armenia, China to Hold High-Level Business Forum,” Xinhua, April 7, 2011. Statistical Yearbook of Armenia-2011 of the National Statistics Service of Armenia contains no data on investments from China in 2010 while estimating the total gross inflows from China in 1998–2010 at a meager $1.3 million compared to Russia and France, which forked over $2.1 billion and $589 million over the same period of time, respectively.

19It won’t be easy to attract Chinese investment into sectors such as software development, given that investment into technology totaled a meager $1.5 billion out of $216 billion that China invested abroad in 2006–2010. In comparison, China invested more than $100 billion into energy and power assets abroad over the same period of time, according to Derek Scissors, “China's Investment Overseas in 2010,” Heritage Foundation, February 3, 2011.

20“Dvykhstoronnie otnoshenia: Kitai” (“Bilateral Relations: China”), web site of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Armenia, undated. Available at http://www.mfa.am/ru/country-by-country/cn/. Accessed on March 15, 2012.

21Iran has been by far the largest recipient of Chinese non-bond investments in 2005–2011 in West Asia, attracting more than $17 billion, with Kazakhstan and Russia trailing behind. Derek Scissors, “China Global Investment Tracker: 2012,” Heritage Foundation, January 6, 2012. Available at http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2012/01/china-global-investment-tracker-2012.Accessed on March 14, 2012.

22When the Russian Navy’s AS-28 mini-submarine got entangled in fishing nets in 2004, a Russian admiral who had attended a U.S.-Russian generals program at Harvard defied SOPs and called a fellow participant from the U.S. side who was at that time working in the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. The phone call, between two men who met at the John F. Kennedy School of Government’s U.S.-Russia Security Program in 2004, began a chain of events that resulted in U.S. and British equipment rushing to the scene and a British undersea rescue vehicle ultimately freeing the AS-28 and saving the sailors’ lives. “U.S. Admirals Talk to Save Sub," Harvard Gazette, October 20, 2005.

23Russia has always balked at expansion of U.S. and EU influence in former Soviet Union, but has been much more tolerant of China’s cooperation with post-Soviet states. In fact, American policymakers may still be debating how to avoid being eclipsed as the sole superpower by the Middle Kingdom, but Vladimir Putin of Russia has already acknowledged the inevitability of China’s rise, noting that Moscow has no plans to quarrel with China over the global domination. “Putin, otkazavshiisya borotsya s Kitaem za mirovoe gospodstvo, smutil Pekin i zastavil obyasnyatsya” (“Putin refused to fight with China for global dominance in what embarrassed Beijing and prompted it to explain its view”), Newsru.com, October 18, 2011.

24As noted above, Sargsyan has been twice to China as a president, but neither were state visits. He first went to attend the opening of the Olympic Games in 2008, and he returned two years later for the opening of the Expo 2010.

25One sign of the level of the current Armenia expertise, if not attention that China pays to Armenia, is that that the web site of the Chinese embassy in Yerevan has Russian- and Chinese-language versions, but no Armenian version.

26Armenian merchants began to trade with China soon after the latter opened its port in Macao for international trade in 1685, and there was a thriving Armenian community in Harbin in the beginning of 20th century. Irina Minasyan, “Kitaisko-Armyanski Kontakty” (“Chinese-Armenian Contacts”), 21st Century, Issue No. 1, 2012, Noravank. Available at http://noravank.am/rus/jurnals/detail.php?ELEMENT_ID=6339. Accesed on March 16, 2012.

27The author could not find ready-to-use projections of the EU’s GDP in 2025 and 2030, so he took the Economist Intelligence Unit’s prediction that the EU’s GDP will grow by some 10 percent in 2010–2015 and extrapolated it to the 2015–2025 period.

Return