28.02.2017

28.02.2017MODERN MIGRATIONS: NEW TERRITORIES, NEW BORDERS

Aram Vartikyan

Assistant Professor, Department of Applied Sociology, Faculty of Sociology, Yerevan State University, Director of Migration Competence Center, Faculty of Sociology, Yerevan State University

Movement from one settlement to another has followed the humankind throughout the whole history. Among the conceptions that address formation, development and fall of civilizations there are specific ones that choose migration as a descriptive element. Probably, there is no single historical period, civilization, state that has not dealt with migration. In this respect, the 20th century is notable, with migration flows taking place since its very beginning period.

Violent displacements, trade, economic, labor, environmental and other migration flows have uniquely formed the vivid process of state and regional developments, as well as the social, economic, political, and most importantly, cultural reproduction characteristics of the former. Migration cycles with their intensity, qualitative and quantitative characteristics have reached their culmination by the last quarter of 20th century and at the beginning of 21st century [29]. Quantitative raise of migration flows, tremendous increase of qualitative diversity, deepening of undeniable and irrevocable influences were caused by fundamental social-historical, geopolitical forces, global, regional developments, changes and processes. Consequently, the raise of global and local uncertainty, asymmetric economic and political activities and processes of separate regions, polarized developments undesirable for the countries, fall of political systems and their remarkable change, extensive forms of financial and economic capital reproduction and accumulation, new division of labor and other resources contributed to the formation of the above described pattern [7]. Changes and developments were no more limited and localized. These being present in a new, strongly interconnected global world have their escalating, often negative, unintended effects on the societies and states that are located in the far corners of the world. In this complex situation modern migration gains its primary importance and significance. As result of global and local social, geopolitical, economic changes and complex processes often being alienated from forming prerequisites, fundamental and secondary factors it becomes a basis for enormous number of socio-economic, cultural and political processes, metamorphoses that cause dangerous and intense uncertainty and tension within social life. It is hard to imagine any state and society, a social group that has not felt the positive or negative impact of migration on itself. Political life of the states and everyday life of individual citizens, ordinary people is deeply flavored with global processes, in particular with the migration seemingly having no direct connection with them. This interdependence, along with migration has led to the formation of global social crater, a member of which is even the population in remote corners of the world. Already formed complex global system is continually expanding, bringing to the growing manifestations of its own and separate features and indicators. In this case, certainly, we may argue that the global migration will increasingly expand both in size and quality encompassing new regions, new social forms and new challenges into its circle. The newly independent Republic of Armenia did not remain apart from diverse processes that engulfed the end of 20th century, unfortunately having mostly negative effects on Armenia. The fall of the Soviet Union, the transition from one quality of economic relations to another, change in the political system that has been formed through decades, the 1988 devastating earthquake, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, economic and energy crisis created unbearable conditions for a newly established state to have a healthy social life [32; էջեր 62-74]. This most difficult situation in Armenia's modern history was manifested in unprecedented migration flows and circulations. Since the last years of Soviet Union and till today the Armenian society has witnessed almost all forms of migration types described in current scientific literature [13].

Indeed, in the last quarter of the 20th century and especially today many social scientists pay attention to the fact that the world is interconnected more than ever [30, 31] . First of all intertwining of information flows is evident. The unprecedented development of information and communication technologies led to a situation that one can hardly imagine a corner where the Western information industry outputs are not present, and what is the most important, something contrasting occurs either [20]. Mass media, social networks etc. each moment deliver political, economic, social, cultural information not only about the West, but also about the states, societies whose existence and geographical location were previously in best cases disclosed only to the professionals [12]. New regimes of global capital growth, new delocalized forms of business bring to the fact that it is almost unreal to have and continue reproducing self-sustained, localized economy without feeling the processes and often tragic effects of changes occurring in distant countries, regions, and integrated economic zones [14]. Political decisions, regional and at a first glance local political processes have sometimes direct impacts on the remote corners of global society. Modern sovereign states and their individual citizens have happened to be in complexly interconnected enormous melting crater of political, social and economic processes in the focus of the crash between global and local reciprocal instability.

Political, economic and social interdependence between regions and states has gained the name of transnationalism [24]. Since in 1960s, mostly in 70s the term was used to describe the features of formation, functioning, development of new economic subjects that represent more than one sovereign state. The discussion is about the so-called transnational corporations that embody the progress that is more flexible and presupposes mostly horizontal ties. Later on the term “transnational” has indicated the weakening of national borders, political institutions and ideas that are linked to them and are present in various spaces [30]. Currently based on the whole diversity of the terms transnationalism it can be concluded that the discussion is probably about the weakening of the meaning of the national borders, which stemmed from the reformation of the global capital accumulation system [25, pp. 49].

In such conditions, the most unique result of transnationalism that has emerged is transnational migration. According to the many supporters of the mentioned idea modern migration with its whole diversity cannot be imagined without taking into account its impact and role in both host and home societies, for the two sides of the separating geographical border [27, pp. 196-204]. Social, economic, political, cultural ties that link the migrant with the host society and the non-migrant in home society have so deepened, spread, intervened the separate social actors’ activities that they have drastically changed the daily life of the individuals, family and community reproduction, traditions, expectations and different attitudes and dispositions. [25, pp 49]: Comparably important and powerful actors, i.e. social, political, economic institutions, and states are not completely isolated from these changes. Meanwhile, the critics of the idea question the novelty of transnational migration and some of its features insisting that they have been related to the previous migration flow types and social developments. They contend that migration and the changes resulted from the transnationalism are not widely spread and refer to a small number of population and will be stopped after one or two generations because the migrants will either assimilate becoming integral elements of the host society or will return to homeland. Finally, a serious criticism is related to the “transnational”, “transnationalism”, “transnational migration” and other similar terms that are often being put in line with the already existent ones, seem to be related to everything, and hence, gaining lower interpretative and analytical meaning [23].

Certainly, the criticism may not be causeless. There are many studies that disclose a variety of aspects of transnational migration, uncover solid samples of relationships and relations of migrants in host and home countries [10, pp. 5328-5335], [22, pp. 547-565], but the question of the dissemination of transnational migration remains unanswered.

Transnational migration practices have a very short history. There is a lack of periodic structured research that would disclose particularly its continuation beyond the generation. And also, are the features of transnationalism and especially transnational migration homogenous in quality or there is a principle heterogeneity of its content depending on the country [27, pp. 196-204]?

At the same time, modern social scientists undoubtedly witness unprecedented changes and processes in the social life, where the increasing transparency of previous and surely more closed borders and the formation of, in a sense, new, inconceivable borders is becoming more evident. Definitely, one needs to be naively brave or incredibly cynical to claim that previous social relationships are rapidly and unequivocally replaced by new ones, a contemporary human being lives in an entirely transnational era [21] and that the traditional mechanisms of the formation and functioning of nation states are rarely encountered and the borders are open for any relationships. On the contrary, we witness an amazing paradox when developments at different levels indicate new borders, absence of any borders, or transformation of borders, while separate states make their border policy stricter for neighbors and immigrants [5]. Under these conditions much more sophisticated research tools and serious attention are necessary to reveal the reality. Thus A. Appadurai states in globalization era social groups are no more territorially predetermined, but are rather unrestricted and highly heterogeneous [1]. Clear-cut territorial borders – traditionally a crucial component of the group and community identity formation – are not of primary importance any more. The modern human being seems to prefer more flexible and mobile components of his/her identity, which could easily be transferred geographically. Over time, these trans-border social networks become so independent and well-formed that they transform into self-reproducing transnational social fields or areas, combining both sending and receiving societies into a single unit. Hence, the economic activity of the included social actors, their political, social, cultural life is mainly formed proceeding from the principles of the transnational territoriality, which interprets the concept of the state in an entirely new way [27, pp. 196-204]

The transnational migrant is one of the actors mentioned, whose daily routine, and short- and long-term future is predetermined by numerous trans-border connections and whose identity is formed under the social and cultural umbrella of more than one territory [18]. Therefore, the members of the social transnational field include and reproduce the social expectations, cultural values and norms, human relations types which are formed as a result of the combination of more than one social, political and economic systems [27, pp 196-204].

But it is not only the trans-migrant who is involved in the transnational social territory and reproduces the appropriate social practice. Obviously the family members of the migrant who stayed in their country and whose life activities are connected and conditioned by the migratory activities of their relative also become part of the transnational social territory. The same is true for the people living abroad who have not visited their homeland for a long time, but somehow are in close periodic touch and continue the interaction. In fact, mobility is not a necessary condition for the transnational migration.

The variety of the transnational migration activities and its diverse manifestations led some researchers to provide the classification of the phenomenon along a number of criteria. So, L. E. Guarnizo differentiates the Core Transnationalism, which is an indispensable part of an individual’s common life, proceeds at certain periodicity. At the same time he puts forward the idea of Expanded Transnationalism, wherein the migrant is not periodically and consistently involved, but rather acts arbitrarily, coincidentally [17]. The other dimension of the transnational migration activities is the scale. Case in point, some people can be involved in the transnational religious activities without any participation in the economic or political activities, while others are involved in all types of trans-border activities. The first is the case of Selective and the second of Comprehensive transnational activity [27, pp. 196-204].

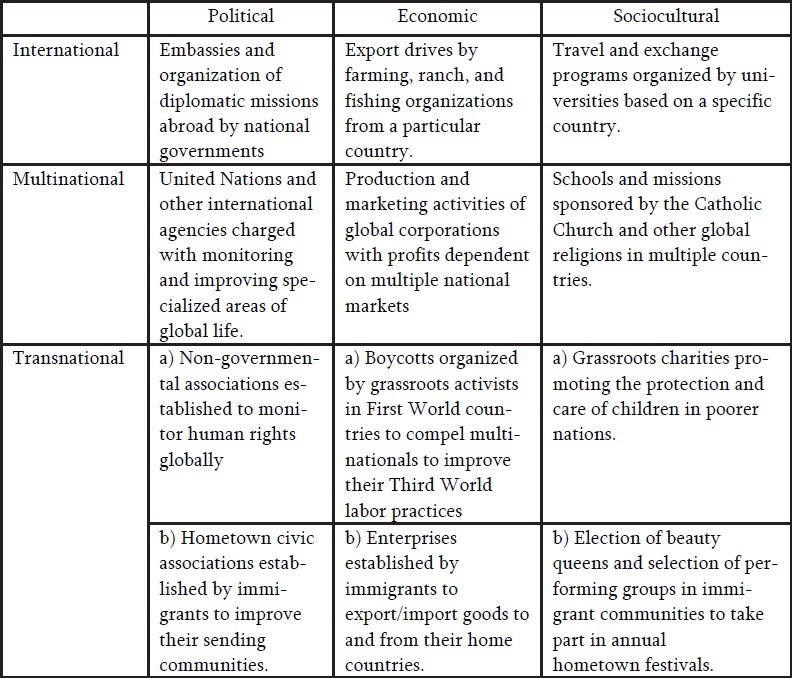

Generally, the definitions of transnationalism and some of its manifestations, main indicators and differences from other trans-border activities are a subject of interest for many social scientists. So, Peter Evans aims at clarifying the differences between International, multinational and transnational by examining their manifestations in the political, economic and social-cultural areas [6, pp. 187].

At the same time disputable is the difference between the transnationalism and globalization and transnational migration. The transnational practice proper and the activities which are the result of modern migration are to be differentiated with a high degree of probability from those which are the result of other global processes [27, pp 196-204]. The problem is that some scholars consider transnationalism – a mutual relationship of people and institutions in cultural, economic, political or many other contexts (entrepreneurship, industry, financial investment, cultural exchange, etc.) [26] – not as a result of modern migration network, but as a direct and indirect result of late capitalism. The transnational migration itself is viewed as a result of the new accumulation ways of goods and flexible modernization typical of late or developed capitalism. It is the result of one of the most deep-rooted phenomena of modern times, namely deterritorialization. The latter, without even presupposing factual mobility of people, changes and transforms the identity of people and groups [4]. Thus, transnationalism reduces and pushes back the role of geography and bordered territories in the formation of collective identity and creates trans-border membership and opportunities for simultaneous social involvement [2]. In its turn, globalization refers to inter-regional and even inter-continental transnational economic, political, social activities and continually strengthens the interaction and interconnection between countries and societies [9]. On a large scale, global processes are not connected with national, state territories, while transnational activities occur in case of more than one, clearly separate countries where the state is not necessarily a transnational actor, but it certainly dominates the activity of others [27, pp 196-204]. A question emerges what lies behind the transnational activities, particularly the progress and continual existence of migration and what is its influence on the receiving and sending societies and countries. According to a number of scholars it was the unprecedented technological advance that contributed to the formation and subsequent gradually deepening functioning of transnational migration network. Available means of communication, quick and cheap transport and particularly the internet were very important for such developments, enabling the current trans-migrant to reproduce its membership and belonging to two state systems. Here there is a danger of vulgar technological determinism, according to which only the emergence and spread of technological means, transport and communication technologies itself leads to a qualitatively new social phenomenon which in its turn comes to transform the whole familiar world and all the social systems. Numerous authors put such simplifications into question, stating that this technological boom is a regular result of deeper economic social, political processes [12]. The newest modes of global capital accumulation, and the changes of processes preconditioned by the latter, makes migrants to live in the centers of global capitalism reproduction, but in line with the transnational life rules. And this leads to the deterritorialization of the economic and social conditions of the receiving and sending societies. However, strange is the still-existent and even more deepening discriminative attitude and profound, inner borders towards the migrants [25, pp. 50].

Today the cultural and social diversity of a number of central and important cities for the modern capitalistic reproduction is especially conspicuous. In the streets of Western megalopolis one can encounter cultural forms, social practices, relations, material and spiritual products, completely non-typical of the West several decades ago, although the migration itself is not a new phenomenon and there have been quite numerous migration inflows before. It seems that newcomers should be free from any integrative controversies, discrimination and social segregation in these conditions of diversity when the picture formed calls forth the freedom and transparency of both internal and external borders. Unfortunately, the opposite paradox is present today. The intensive increase of migratory flows and the diversity of migrants in the traditional and newly formed receiving societies and, at the first sight, the global interdependence of countries are accompanied by the gradual fortification of external borders and inner predicaments. The impossibility of painless assimilation and integration, marginalization of numerous migrant groups, social exclusion and the further stagnation of mobility result in various, and often ferocious conflicts. The vulnerability of immigrants is currently defined by a special term known as the Ulysses syndrome [3]. Without mastering the formal mechanisms for the improvement of the situation, immigrants form unique vital strategies where the transnational social practices and networks are of primary importance. Seemingly arbitrary and chaotic immigration acts, when reaching a certain “critical mass” establish ground for the further self-reproducing non-formal, trans-border network, through which new compatriots are attracted to the receiving society. At times the social networks construct logical junctions in the receiving states in the form of new transnational communities [8, pp. 583-599]. The local activity of the communities, links with the homeland, stable relationship of certain migrants with the relatives in the country of origin come to form a system of mutual help, which in many cases reduces the shock of newcomers and the tragic process of the arising problems. On the other hand, the transnational membership and practice formed, new communal activities and links with the country of origin may lead to the decrease of integration potential in the receiving society, casting doubt on the assimilation approaches and formal policies. The traditional approach, according to which to become a full-fledged member of the receiving society, one has to re-socialize, accept and assimilate and later to reproduce the values and norms of the receiving society, its behavioral forms, which in the western societies are based on the class, state-national ideology and loyalty principles [19]. Thousands of immigrants for years live and conduct activities being an integral part of transnational social community and territory, of the far country of origin.

The mechanisms of the transnational territory reproduction and continual proliferation are present in the sending society as well. A number of researchers noted that emigration, having once started, tends to continue even though the initial reasons for it have been reduced or are even absent. The phenomenon referred to as cumulative causation, migrant syndrome and so on, indicates that the initial migration act leads to such a change in the social-economic context that the further migration acts become more preferred and reasonable [11, pp. 1492-1533], [15, pp. 56-66]. The transnational territory being formed and trans-border social network evidently assists the process. Due to the remittance from abroad the families of migrants find themselves in more beneficial conditions, other things being equal. The working social network consisting mainly of friends and relatives, which provides the predictability of emigration and reduces the risks, contributes to this process. The transnational migration practice provides the accumulation and consumption diversification of risks, expenses and resources.

The complicated situation formed requires a fresh interpretation and reformulation of the concept of diaspora. Within the framework of social discourse the diaspora is represented as a group of marginalized people who lost their country of origin as a result of violence and those who anticipate homecoming, at least at the initial stage of the diaspora formation [16, pp. 3-36]: The Armenian so-called traditional diaspora communities, which were formed mainly after the 1915 Genocide, were always singled out by unity and solidarity, having as their ultimate goal the preservation of the Armenian outside Armenia [34]. Having passed through assimilation processes for the whole 20th century, the latter exhibited a high degree of integration potential. The representatives of diaspora occupied a number of significant social-economic and cultural niches and high social positions in many countries. Gradual membership in the receiving societies, with a definite preservation of the Armenian identity, has weakened ties with the motherland, namely the Republic of Armenia, which was the country of origin only for a small fraction of the diaspora Armenians. This resulted in the preservation of mere symbolic emotional ties, the functioning of which manifested itself only from occasion to occasion, especially at tragic times for the Armenian people. The Soviet Iron Curtain also had a role to play in this kind of ties manifestation. Under such conditions the feeling of belonging and membership was ambiguous: a. member of the Armenian diaspora, b. citizen of the receiving country and a full-fledged member of the society [33]. The new transnational communities, formed after post-Soviet era, were already different both geographically and in essence. Firstly, preservation of the Armenian outside Armenia was not the primary point on the agenda. The life responsibility was much narrower, since the community could be an assisting link when conducting certain economic activities. Apart from it, evident are the stable, periodic ties with the country of origin including almost all the spheres of the social life, which leads to the double belonging and membership, where the country of origin is the primary link. In this way the formula of “simultaneously here and there”, as well as “neither here, nor there” emerges. Thus, the modern Armenian diaspora is a group of Armenians, residing abroad, comprising both traditional communities and transnational communities, actively or passively reproducing the ties with the country of origin. The problem of ambiguous belonging, present also in current Armenia, becomes evident when examining a number of transnational practices. When the receiving society, upon realizing the realistic or concocted perils to the social progress or stable cultural reproduction, restricts the national and political border policy, numerous sending countries, including the Republic of Armenia, switch to a new regime of power, state and social relations. The transnational and trans-border ties acquire obvious and major importance in the given situation.

The transnational economic activities are not constrained to individual remittances to families. The state and communal investments reach high volumes. Many successful emigrants begin reconstructing communal rural substructures, building schools, kindergartens, churches and so on. This is indicative of an intensive feeling of belonging and loyalty to the community, village, and the former place of residence. The concept mentioned is also confirmed by the obvious visualization of investments necessary for increasing or reproducing the social status in the country of origin. Definitely it could be claimed that the transnational economic activity and the continual monetary inflows free the administrative bodies from responsibility, nonetheless the new model state and nation formation is evident. The transnational political activities come to corroborate this. Many sending countries see the need for goal-oriented participation of a vast number of emigrants in their internal and external political processes. In the case of Armenia the problem is particularly important in that the number of Armenians residing abroad outnumbers those living in Armenia, and this resource needs utilization. Providing to the Armenians residing abroad the right for vote and political will expression, the political elite consolidates the democratic essence of the country [27, pp 196-204]. Besides, the electorate in this case may provide a significant help for this or that political power or party. The question of political belonging and legitimate rights arises here. To what extent the compatriot living abroad can be responsible for the processes occurring in the country of origin, be well-aware of them and make an unbiased decision and express his will freely? Certainly the contemporary means of communication and the Internet provide a partial solution to the problem. A more comprehensive solution is the dual citizenship practiced in Armenia [28]. And it is here that the problem of national belonging and its application moves to the forefront in the contemporary global society.

In summary, it can be stated that although the traditional nation-states have not only not weakened the traditional modes of reproduction, but rather in the conditions of current local and global tension, security threats and uncertainty have consolidated and deepened them, posing additional limitations and barriers. However, the formation of new borders, the new ways of national borders perception and application cannot be ignored any more. The transnational social territories and the transnational migration within them, as well as the social, political, economic activities with numerous empirical manifestations, are a vivid confirmations of this fact.

November, 2016

References

1. A. Appadurai, Global Ethnospaces: Notes and queries for a Transnational Anthropology, Recapturing Anthropology, ed. R. Fox, Santa Fe, School of American Reserche Press, 1991.

2. A. Appadurai, Modernity at large: dimensions of globalization, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

3. A. L. Diaz-Cuellar, H. A. Ringe, D. A. Schoeller-Diaz, The Ulysses Syndrome: Migrants with Chronic and Multiple Stress Symptoms And the Role of Indigenous Linguistically and Culturally Competent Community Health Workers, [online] 2013. (http://www.panelserver.net/laredatenea/documentos/alba.pdf, accessed 9 August 2016).

4. A. Ong, D. Nonini (eds.), Ungrounded empires: the cultural politics of modern Chinese transnationalism, New York: Routledge Press 1997, pp. 3–33.

5. A. Pecoud, P. Guchteneire, Migration Withot Borders, Essays on The Free Movements of Peoples, Unesco, 2007.

6. A. Portes, Introduction: the debates and significance of immigrant Transnationalism, Global Networks, 2001, Volume 1, Issue 3, pp. 187.

7. A. Solimano, International Migration in the Age of Globalization, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

8. B. Riccio, From «ethnic group» to «transnational community». Senegalese migrants’ ambivalent experiences and multiple trajectories, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 2001, Vol. 27, No. 4: 583-599.

9. D. A. Held, D. McGrew, D. Goldblatt, J. Perraton, Global Transformations, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999.

10. D. S. Massey, R. M. Centeno, , The Dynamics of Mass Migration, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 1999, Vol. 96, pp. 5328-5335.

11. D. S. Massey, L. Goldring, J. Durand, Continuities in Transnational Migration: An Analysis of Nineteen mexican Communities, American Journal of Sociology, 1994, Volume 99, Issue 6, May, 1492-1533.

12. F. Webster, Theories of the Information Society, Rootledge, 2006.

13. G. Pogossyan, Migration In Armenia, Yerevan, 2003.

14. G. Ritzer, Globalization, The Essentials, Wiley, 2011.

15. J. S. Reichert, 1981, The Migrant Syndrome: Seasonal US. Wage Labor and Rural Development in Central Mexico, Human Organization, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 56-66.

16. K. Tololyan, 1996 ‘Rethinking diaspora(s): stateless power in the transnational moment’, Diaspora, No 5, pp. 3–36.

17. L. E. Guarnizo, Notes on Transnationalism, Paper for Conference: Transnational migration: Comparative theor and Research Perspective, Oxford, UK, 2000.

18. L.G. Basch, N. Glick Shciller from, C. Blanc-Szanton, Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterriorialized Nation States, New-York, 1994.

19. M. Boatca, Class Vs. Other As Analityc Cathegries: The Selective Incorporation of Migrants Into Theory, T. Jones, E. Mielants, Mass migration in the World System: Past, Present And Future, Paradigm Publisher, 2010.

20. M. Castells, The Rise of the Network Society, The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture Vol. I. Cambridge, MA; Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1996.

21. M. I. Angulo, National Identity or Transnational Citizenship? In T. Jones, E. Mielants, Mass migration in the World System: Past, Presnt And Future, Paradigm Publisher, 2010.

22. M. Kerney, The local and the global: the anthropology of globalization and transnationalism, Annual Review of Anthropology, 1995, No 24, pp. 547-565.

23. M. Suarez-Orosco, Commentary, Papers of Transnationalism and Second Generation Conference, Harvard University, 1998.

24. N. Al-Ali, K. Koser, New approaches to Migration, Routledge, 2002.

25. N. Glick. Schiller, From Immigrant to Transmigrant: Theorizing Transnational Migration, Anthropological Quarterly, 1995, Volume 68, Issue 1, pp. 49.

26. N. Nyber Sorensen, Notes on transnationalism to the panel of devil’s advocates: transnational migration – useful approach or trendy rubbish?’ Paper presented at the Conference on Transnational Migration: Comparative Theory and Research Perspectives, ESRC Transnational Communities Program, Oxford, UK, June, 2000.

27. P. Levitt, Transnational Migtaion: Taking Stock and Future Directions, Global Networks, 2001, Volume 1, Issue 3, pp. 196-204:

28. Republic of Armenia Low on Dual Citizenship, http://www.mindiaspora.am/en/erkqaghaqaciutyun

29. S. Castles, M. J. Miller, The Age of Migration, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

30. S. Vertovec, Transnationalism, Routledge, 2009.

31. T. Faist, M. Fauser, E. Reisenauer, Transnational migration, Wiley, 2013.

32. Ա. Վարտիկյան, Միգրացիոն հոսթերի ուղղությունները և դրանց հետևանքները, Միջազգային գիտաժողովի նյութեր, ՀՀ ԳԱԱ, Երևան, Գիտություն 2006, էջեր. 62-74:

33. Ա. Վարտիկյան, Հայկական hետցեղասպանական սփյուռքի առանձնահատկությունները, Ցեղասպանությունը հասարակական գիտությունների կիզակետում, Հոդվածների ժողովածու, ԵՊՀ, Երևան 2015, էջեր:

34. Հայ սփյուռք հանրագիտարան, Հայկական հանրագիտարան հրատարակչություն, Երևան, 2003թ.

Return