18.06.2015

18.06.2015STRATEGIC RESEARCH CENTERS IN TURKEY

Arestakes Simavoryan

Head of the Centre for Armenian Studies, Noravank Foundation

Systemic development of strategic research centers1 (SRC) in Turkey started in 1960s2. Among the Middle Eastern countries Turkey probably has the oldest think tanks along with Israel3. Among the various research areas and directions they also study the development traits, typology, strategic priorities and other aspects of the Armenian think tanks.4

The period of extensive development for SRCs in Turkey started in 2002, when the Justice and Development Party (Turkish: Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, or AKP) came to power. New and narrowly specialized expert/analytic institutions were established in the last decade, which was prompted by geopolitical and regional developments, new conflicts, crises of different types and other problems, as well as the need to overcome barriers between practical politics and academic science, and to influence the decision-makers. The essential function of Turkish SRCs is to present ideas/proposals, develop strategic programs, development visions, political and military forecasts with regard to national security issues, and most importantly, deliver those to the decision-makers.

Before the collapse of the USSR there were very few SRCs in the “market of ideas” in foreign policy, which were involved in development of conceptual and strategic visions and had little influence on decision-makers. Conversely, today the government entities and other actors make use of their studies and analyses for implementation of practical politics, especially in foreign policy and security. The SRCs also contribute to development and strengthening of Turkey’s diplomatic efforts. In addition, it has to be mentioned that frequent visits and lectures of Turkish government officials at SRCs are becoming an integral part of the activities in this area.5

Turkish experts are increasingly included in government delegations visiting foreign countries, in order to provide “intellectual support” to the government officials and to build international cooperation bridges with think tanks of these countries. It speaks volumes that in the recent years the Turkish political leadership has publicly mentioned numerous times the significance and role of the think tanks not only in foreign policy, but in all areas.6

According to the data of 2014 Global Go To Think Tank Index Report there are 31 strategic research centers in Turkey.7 However, during our studies we have identified about 150 research centers. Perhaps, out of their own methodological considerations the US researchers have not included most of them in the list due to the instable and ineffective work of many of these centers.

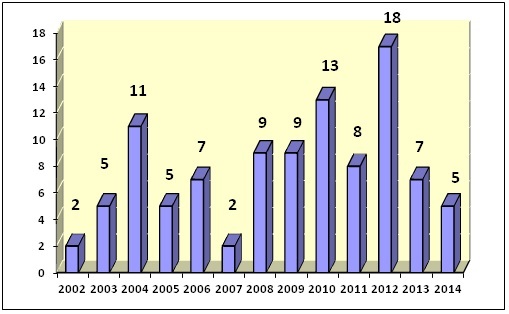

Since 2000 the number growth rate of SRC has been sharply declining worldwide and in 2004 it receded to mid-20th century levels. Experts explain this by natural “saturation” of the SRC market.8 Yet in Turkey the number of research centers skyrocketed since 2002, when Justice and Development Party led by Erdogan came to power. We calculated that in the period between 2002 and 2014 from 2 to 18 new centers were established annually (see Figure 1). Such rapid advancement can be viewed as a sign of a newly developing industry in the country.

Figure 1

The number of established SRCs in Turkey per annum

Most of the analytical institutions established in 2002-2014 implement studies in foreign policy of Turkey. The second largest group consists of those involved in research support of government economic policies. Expert assessments and analyses are implemented in areas that were not deemed important in the past or the work done there was considered insufficient or they were not seen relevant in the perspective of facing the contemporary challenges (e.g. issues related to such areas as education, environment, information, national security and society).

In terms of affiliation, the Turkish SRCs can be divided in several categories:

1. Government affiliated (6 centers, including, e.g. Turkish Grand National Assembly Research Centre),

2. Party affiliated (4 centers, including, e.g. the Political and Social Studies Foundation),

3. Private (130 centers, including, e.g. Foundation for Economic Development and Strategic Research),

4. Branches of foreign centers (9 centers, including, e.g. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Turkey),

5. Affiliated to educational/academic institutions (including, e.g. Center for Strategic Research of the Ankara University).9

HR Policy

Depending on the demand for research directions, SRCs recruit young people with higher education (master’s degree) from academic institutions, those with PhD degree, as well as doctors of science in political studies who have studied abroad, and honorary members of academies of science. SRCs also recruit retired military officers, statesmen, politicians and diplomats. In a closed-doors meeting between Abdullah Gül, former Turkish president and staff of the Ekopolitik Center for Economic and Social Research, Vamık Volkan, a consultant of the center at the time and psychoanalyst told the president: “Among us we have both former members of National Intelligence Organization and a Kurd who just descended from the mountains”.10 In any case personnel recruitment remains one of the most important challenges that the Turkish SRCs face. Neither the government, nor the private sector had created the necessary work environment to train such personnel. For this reason the choice of potential employees had been limited in the past and remains such in the present. Many experienced specialists work part-time in several centers. Very often the presidents and directors of SRCs are selected among public activists, former diplomats and the like, who enjoy respect in the country, as well as business people.

Turkish scholars report that the work contracts with the experts are usually short-term, whereas long-term contract are made only when 2-3 years long special research programs have to be carried out. It is often pointed out that short-term contracts are not too useful when one tries to fully integrate young specialists into analytical work.11

The more savvy centers make use of Turkish “diaspora” scientific and expert resources in order to make them aware of the state’s primary problems and mobilize them for common goals. There are several leading SRCs that have consolidated Turkish intellectuals residing in foreign countries around various political platforms and institutions. Most of the experts focus their potential on regional issues of Middle East, Balkans, and Caucasus, which implies that all these issues are integral part of Turkish foreign policy. This approach of the centers aims at being close and catering to the government, present themselves as “defenders” of the country’s foreign policy processes and thus, help their organization survive. In any case, the problems “producing” and “growing” intellectual resources and limited financial capabilities still remain acute for the sector.

The Ideological Component

Regardless of who is in power, the centers involved in foreign policy studies have started to act under influence of ideologies and try to establish business relations with various government organizations, including security, defense and law enforcement agencies.

Among the centers that adhere to conservative ideology and have close relationship with the ruling party the following can be mentioned: the Foundation for Political, Economic and Societal Research (Siyaset, Ekonomi ve Toplum Araştırmalar Vakfı-SETA – established in 2006)12, and Institute of Strategic Thinking (Stratejik Düşünce Enstitüsü-SDE – established in 2009).

There are centers adhering to other political movements that support the ruling government, such as the conservative nationalist Turkish Asian Center for Strategic Studies (Türk Asya Stratejik Araştırmalar Merkezi-TASAM – established in 2004), and the liberally inclined International Strategic Research Organization (Uluslararası Stratejik Araştırmalar Kurumu-USAK – established in 2004) which is close to diplomatic, military and political circles. Many speeches by AKP members of parliament, Turkish statesmen-members of international organizations and especially president Erdogan are based on the research conducted by these centers. As Sedat Laçiner, former General Coordinator of one of the reputable Turkish think tank International Strategic Research Organization has noted: “We call ourselves liberals and patriots. The Government and AKP preserve the values acceptable to us, but we support the policy that is in line with our viewpoints”.13

There are also nationalistic (pan-Turkic) centers, such as the Turan Strategic Research Center (Turan Stratejik Araştırmalar Merkezi (TURAN-SAM – established in 200714), and the 21st Century Turkish Institute (21 Yüzyıl Türkiye Enstitüsü - establshed in 2005), which differs from many others by variety of regional and thematic studies15, and implements contracts for certain political circles and ultra-right parties. Nationalistic domination in this institute is evidenced by the articles published in the 21st Century quarterly analytical journal, where new phrasings characteristic to pan-Turkism can be found, such as “Turkish super-ethnos”. The idea of “Turkic oil” similar to “Arab oil” is circulated, which supposedly should become one of the strategic factors for the Turkic world in the future global energy crises.

There are also SRCs adhering to liberal, neoliberal and ultra-liberal, Islamist, Gulenist, Kemalist and Turkish Eurasianist ideologies that produce “intellectual products” of these kinds.

Non-ideologized SRCs attempt to maintain neutrality in their relations with political actors and deliver messages to the government through media, TV companies, personal connections, etc.

Complexities in the Government-SRC Relations

Although the decades-long atmosphere of conflict and “intolerance” 16 in government-SRC relations was partially overcome, but the government’s attitude toward some extremely ideologized SRCs has changed, especially with regard to those harshly critical of the government foreign policies. The ideologized SRCs that had close relations with the military fell under scrutiny of law enforcement agencies in connection with the Ergenekon case, with some heads of centers arrested and offices searched. After several leaders of Turk Metal trade union were arrested, the Turkey’s National Security Strategic Research Center (Türkiye Ulusal Güvenlik Stratejileri Araştırma Merkezi – est. 2004) founded by the mentioned trade union ceased to exist. It had leftist nationalist inclination with some close relationships ultranationalist military circles.

A serious blow was dealt to Ülker Group financed ASAM (Center for Eurasian Strategic Studies), an institution representing itself as “soft power” of the military and intended for activists of Turkish armed forces and Nationalist Movement Party, the main weapon of which is the Institute for Armenian Research (Ermeni Araştırmaları Enstitüsü). Some Turkish scholars believe ASAM’s closure could have been related to the economic crisis17, while some others attribute it to political reasons.18 WikiLeaks points to political calculations with regard to closure of ASAM, calling it “a blow to intellectual freedom in Turkey”.19 It can be stated that the shutdown of this center was carried out more smoothly and its political aspect was not made public.

The Ergenekon case of 2009 also prompted closure of the Center for Political, Economic, Social Studies and Strategic Development (SESAR) and the Verso Center of Political Research.20

In 2002 the Strategic Research and Studies Center (Stratejik Araştırma ve Etüt Merkezi-SAREM) was established attached to the Turkey’s General Staff as an “idea-generation unit” to influence military planning decision-makers. The center researched three main topics: Turkish-Greek relations, Northern Iraq and Kurdish problems. The military founded this research structure citing the need of new concepts and approaches, as the old ones were no more sufficient for Turkey in the era of network-centric warfare. Although the leadership of the General Staff declared from the very beginning that internal political matters of Turkey are outside the interests of the center, however, in its analytical articles the center harshly criticized the APK, especially for the latter’s stance on the Kurdish issue. After all this, in the framework of the Operation Sledgehammer coup d’état plan case, the former head of the center Süha Tanyer was arrested and in 2011, a few months before national elections the center closed down with explanations offered.21

It can be thus stated that the SRCs providing intellectual support to the military elite were viewed by the AKP government as “lairs of revolutionaries”.

In summary it has to be noted that although there are many issues in the area, but the Turkish analysts’ community makes efforts to bring an active milieu to the work of the centers established earlier, withstand competition, export “intellectual products” to the international market, as well as attempt to establish new centers in line with modern standards.

1 This equivalent of “think tank” wording in Turkish language was introduced in 1990s. Before that there was no common name, even the western “think tank” was not used. The following terms used in Turkish language are “düşünce kuruluşlar” – translated as intellectual structures, “düşünce merkezleri” – intellectual centers, “Stratejik Araştırmalar Merkezi” – strategic research centers, etc.

2 Սիմավորյան Ա., «Թուրքիայի ուղեղային կենտրոնների զարգացման նախադրյալները. այժմեական խնդիրները», «21-րդ ԴԱՐ», #6, 2012, նույնի՝ «Թուրքական վերլուծական կենտրոններ. տեսություն և արդիականություն», «Գլոբուս. ազգային անվտանգություն», 2009, թիվ 3։

3 Eric C. Johnson, “Policy Making Beyond the Politics of Conflict: Civil Society Think Tanks in the Middle East and North Africa”, in Think Tanks and Civil Societies: Catalysts for Ideas and Action, eds. James G. McGann and R. Kent Weaver, (New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 2000), p. 339-340.

4 Oya Eren, Ermenistan’da think-tank’lar, Hasan Ali Karasar, Hasan Kanbolat, «Avrasya'da Stratejik Düşünce Kültürü ve Kuruluşları», 2012, s. 11-23.

5 Türkiye’nin yönünü tartışmak bilgisizlik, http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/gundem/12861769.asp (5 Kasım 2009).

6 Hasan Kanbolat, Prime Minister Erdoğan and Turkish think tanks, http://www.todayszaman.com/columnist/hasan-kanbolat/prime-minister-erdogan-and-turkish-think-tanks_307437.html (February 18, 2013).

7 2014 Global Go To Think Tank Index Report, Philadelphia, PA USA, February 4th, 2015, p. 56.

8 Հարությունյան Գ., «Ուղեղային կենտրոնները» և ազգային անվտանգությունը, 21-րդ ԴԱՐ, #1(35), 2011, էջ 10։

9 According to various assessments there are over 80 SRCs in the system of educational/academic institutions.

10 Gül Ekopolitik Grubu ile görüştü, http://www.haberturk.com/gundem/haber/546127-gul-ekopolitik-grubu-ile-gorustu, (26 Ağustos 2010).

11 Bilal Karabulut, Dünyada Ve Türkiye’de Think Tank Kuruluşları: Karşılaştırmalı Bir Analiz, Akademik Bakış, Cilt 4, Sayı 7, Kış 2010, s. 101 և Hasan Kanbolat,“Türkiye’de Düşünce Merkezi Kültürünün Oluşum Süreci: Türkiye’de Dış Politika ve Güvenlik Alanındaki Düşünce Merkezleri”. http://www.orsam.org.tr/tr/yazi goster. aspx?ID=32325.08. 2009.

12 This organization was established based on Ankara Center of Turkey’s Political Studies (Türkiye Politik Araştırmaları Ankara Merkezi-ANKAM – established in 2003).

13 Wendy Kristianasen, Les think tanks turcs, agents du changement, Le Monde diplomatique, Février 2010:

14 Established by Dr. Elnur Hasan Mikail, Foreign relations expert, who have migrated from Azerbaijan to Turkey (http://www.turansam.org/yonetim.php).

15 The issues related to Turkey’s information security, development and modernization of internet and hi-tech/biotech industries are considered especially urgent matters.

16 For many years Turkish authorities had an adverse attitude towards the organizations studying serious problems of internal and foreign policies, because they believed any issue related to foreign policy is their own business only.

17 Muharrem Sarıkaya, Davutoğlu ASAM'da hesapları bozdu, http://www.haber7.com/siyaset/haber/359083-davutoglu-asamda-hesaplari-bozdu (18 Kasım 2008).

18 ASAM’dan nankörlük, https://vakityazilari.wordpress.com/2008/11/18/asam%E2%80%99dan-nankorluk/.

19 Turkey: Premier Think Tank ASAM Closes Its Doors, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08ANKARA2070_a.html.

20 Established in 1989 by Erhan Göksel, chief advisor to Turgut Özal.

21 Askerin 'beyni' durdu!, http://www.radikal.com.tr/turkiye/askerin_beyni_durdu-1076174.

Return

Another materials of author

- ANTI-ARMENIAN ACTIVITIES OF THE UNIVERSITY “ARMENOLOGICAL” DEPARTMENTS AND ANALITYCAL CENTRES IN TURKEY[15.03.2017]

- ANTI-ARMENIAN ACTIVITIES OF THE UNIVERSITY “ARMENOLOGICAL” DEPARTMENTS AND ANALITYCAL CENTRES IN TURKEY[15.12.2015]

- CENTERS FOR ARMENIAN STUDIES IN EUROPE[24.02.2015]

- PROBLEMS OF THE CENTERS FOR ARMENIAN STUDIES AND THE WAYS OF THEIR SOLUTION[22.01.2015]

- THE ARMENIAN ISSUES IN THE AGENDA OF THE THIRD WORLD TURKIC FORUM[18.09.2014]

- THE ARMENIAN SCIENTIFIC AND ANALYTICAL COMMUNITY IN THE USA[06.03.2014]

- ANALYTICAL COMMUNITY OF THE DIASPORA AS A POTENTIAL FOR THE COUNTRY: INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE[13.01.2014]

- ARMENOLOGICAL CENTERS IN THE DIASPORA AS INSTITUTIONAL INTELLECTUAL RESOURCE[08.10.2013]

- TURKEY ON THE THRESHOLD OF 2015[11.07.2013]

- SCHOOLS OF THE ARMENIAN CATHOLIC COMMUNITY IN ISTANBUL[06.06.2013]